Tiny fragments of space debris pose threats to operating satellites and spacecraft. Researchers are building a platform to track them and predict their movements.

By Jean Thilmany

Your desk isn’t the only cluttered space in the universe. A growing amount of “space junk,” the cast-off pieces from nonworking satellites, is orbiting Earth and it’s predicted to cause big problems in the coming years.

Even a glancing blow from a tiny piece from an old satellite could damage or destroy a working satellite, possibly affecting national security issues and commercial services on Earth.

Almost 5,500 satellites orbit the planet, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, with the potential for another 58,000 by 2030. About 3,000 of those are no longer in service or “dead,” according to the United Kingdom Natural History Museum.

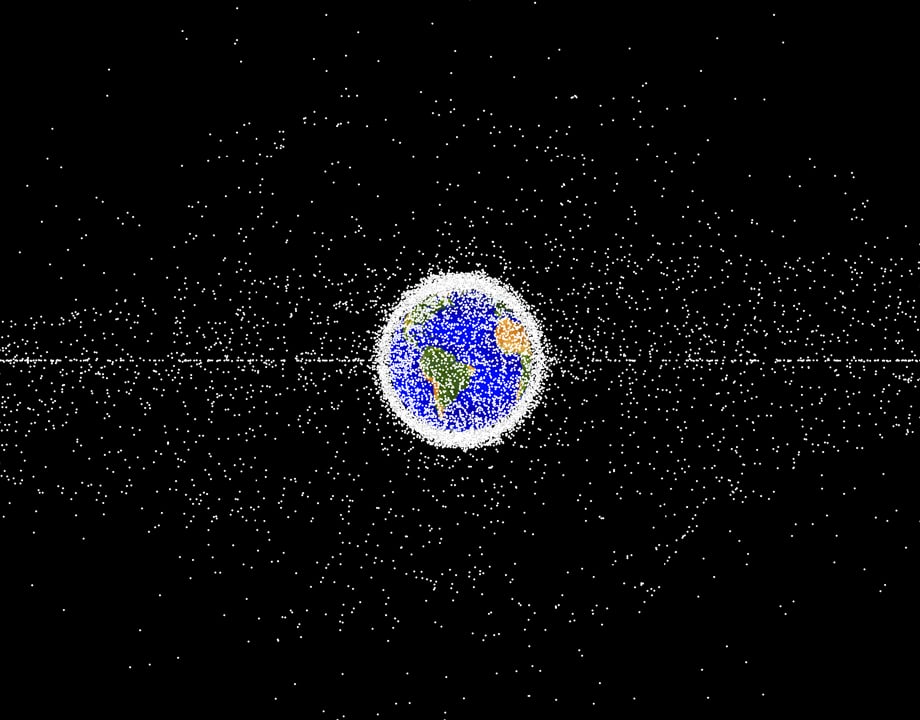

NASA data shows debris orbiting Earth. About 95 percent of the objects in the image are space debris. Image: NASA

The dead satellites float in space with no one controlling them, leaving them vulnerable to collisions with space junk, which results in even more space junk. Even tiny pieces can be disastrous for fragile satellite components, according to the museum, which estimates there are currently some 128 million pieces under one millimeter in size floating in orbit.

“Space is becoming more and more crowded and solutions becoming more and more urgent, said Ming Xin, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of Missouri, in Columbia.

“Space degree is not controllable,” he added. It’s not measured nor is it even followed from stations on Earth.

Xin’s research team is investigating how to predict the movement of space objects accurately without measurement and without observation. The researchers are building a machine-learning model populated with historic and current sensing data for space objects.

The digital model is intended to track space objects and predict behaviors such as their speed and trajectory. The model could then pinpoint potential collisions that could send new debris and particles into orbit.

By its very nature, the machine-learning algorithm gets better and better at predicting the future position and velocity of those objects. The researchers will program the model with new measurements, as they come in, Xin said, adding that the program will be unique in its ability to predict potential crashes.

While studies are underway on best practices to remove space debris, right now there’s no good method to know exactly what’s out there, he said. That’s because once a satellite is no longer in use, it stops being controlled.

“It’s like putting tens of thousands of vehicles on a highway system without any signage or traffic regulations,” Xin said.

The model could help determine best remediation strategies such as sending objects into high orbits away from Earth or bringing them closer to our atmosphere to burn, he added.

At present there is a centralized system that tracks when satellites are launched, along with ground radars and orbital sensors. But tracking is limited, Xin said.

“They can’t keep up with the increasing number of satellites being launched into space,” he said.

Jean Thilmany is a science and technology writer in Saint Paul, Minn.